What to do if you can’t go AI Sober

Some questions to help you stay loyal to your values as AI accelerates

A few weeks ago I wrote about why I am personally not using generative AI at all (as far as I can avoid it). I use the phrase “AI Sober” to acknowledge that I don’t necessarily think gen AI is aways (essentially) a poison, but that it is potentially addictive and it may not be that good for a lot of us. I have now dropped the paywall for that post so it is free to read in full.

Being able to avoid gen AI is a privilege. I mainly work for myself, and make the podcast I host, The Sacred with Theos, an organisation who have done a lot of deep thinking about AI and are therefore unlikely to impose it on me. This gives me a level of freedom and power that I do not take for granted. It may not be possible for you to avoid gen AI completely, or you might want to figure out a position whereby you can get the benefits without compromising your values. I am also aware that if my worklife changes (if, for example, making a living as a public communicator becomes even more precarious, partly because of AI) I may not be able to maintain my hardline position forever.

Thoughtful organisations have already been doing at least some reflection around the question. This, for example, was sent to me by the CEO of Summerdown, a company who make lovely things with mint.

You can hear the ethical concern bubbling underneath: what is a human? What is uniquely our job? What is it ok to relinquish capacity and responsibility for, and when should we fight for it?

It goes further in its ethical reflection than many similar documents I have been wading through this week, most of which focus solely on privacy, security, potential offence, inclusion and biases. All good things to think about, but there is usually no (at least explicit) vision of the human being and how we might be changed by the use of these technologies. Or in my language, no understanding of formation, that we are what we repeatedly do.

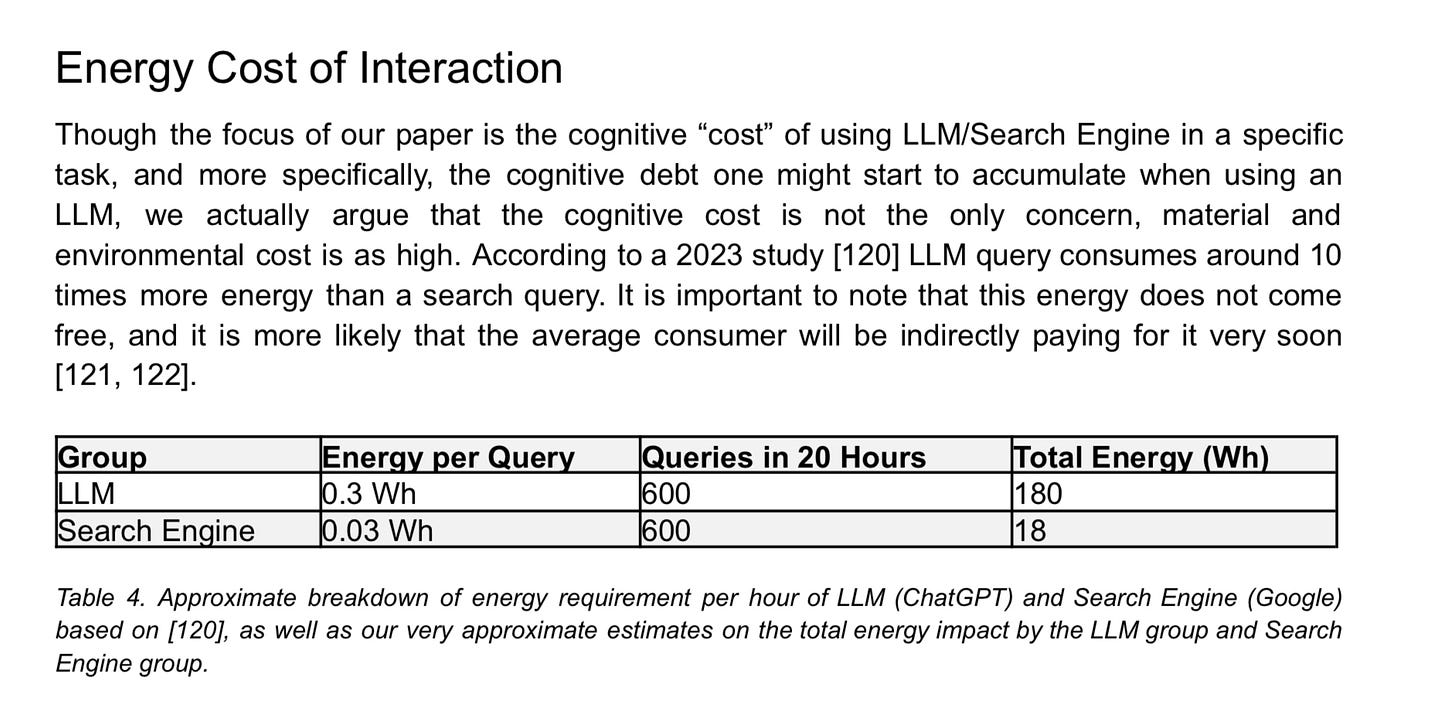

There is also very rarely an acknowledgement of the environmental impact of gen AI. I am not going to wade into the disputes around this, and will just mention that one recent MIT study on the cognitive debt caused by using large language models in essay writing found they required 10 x the energy use of a standard search engine. The whole study makes illuminating and alarming reading.

If you’re someone whose values are grounded in a theological framework, or you’re curious about that approach, you may find this piece from Andy Crouch useful. He lays out a Christian understanding of the human in relation to technology and then finishes on a vision of a “redemptive AI” that would meet the following criteria. Wherever you ground your values, it seems a healthy summary to me:

Redemptive AI would:

inform but not replace human agency.

develop rather than diminish human cognitive capacity and extend rather than replace education.

respect and advance human embodiment.

serve personal relationships rather than replace them.

restore trust in human institutions by protecting privacy and advancing transparency.

benefit the global majority rather than enrich and entrench a narrow minority.

Even as I copy this out, my scepticism is rising. The best funded, most accessible products currently flooding the market do not appear to me to meet many, or in some cases any of these criteria. This could of course be seen as be an argument for more engagement in this space by building alternatives, rather than a reason to avoid it completely. I know some of you are already attempting to do that, and I’m grateful for you. We’ve always needed refuseniks to encourage others to caution and then people prepared to roll up their sleeves and build something better.

Whether you are currently steering clear or trying to find a way to use these tools in humanising (or less dehumanising) ways, here are some questions that are always generative, whatever we are trying to find wisdom for:

What are my values?

Not everyone loves the concept of values. They have certainly been hollowed out through vacuous corporate usage. You might prefer virtues or principles. Either way, these deeper, non-instrumental, non-contingent commitments are the bedrock of a meaningful life and should be a fundamental in all our decision making. They form the backbone of my coaching practice. You may already know, but if not, spend some time reflecting on these questions and see what emerges.

What is sacred to you?

Who do you admire, and why?

What stories do you find inspiring?

What do you find morally beautiful?

What do you think defines a good life?

What would you like people to be able to say about you at your funeral?

What makes you angry? Why?

A failure to understand our values leaves us open to being solely reactive, making calls based on the immediate benefits of speed, efficiency, comfort, convenience and cheapness. Ugh, I am finding writing this convicting. I lost my patience filling in a form to get on the internet in a cafe the other day, because it was taking more than thirty seconds. The idea of spending more on an ethical, quality product is good in theory but when presented with budgetary realities so often goes by the wayside. None of these instrumental goods are necessarily negative, and sometimes they are absolutely fine to let them lead us. Trouble is, we have surrounded ourselves with systems constantly reinforcing them as the only criteria we need. This is at least partly what has driven so many do the collective problems we do not now know how to solve. Meaningful, beautiful, liberated lives almost always require a willingness to sacrifice instrumental goods in service of something bigger and longer term. If we don’t build and maintain this muscle, keep our values up front in our consciousness, the short-term instrumental stuff slowly locks us into a prison of our own making. No-one ever set out to have “she lived efficiently, cheaply and rarely tolerated inconvenience or discomfort” on their tombstone, but we are repeatedly invited to live as if that was indeed our aim.

Who do I want to be becoming?

There are many external incentives in workplaces, schools and social life. Grades, money, progression, acclaim: none of these things are irrelevant. Through a values lens though, they are also not ultimate.

We are what we repeatedly do. The way we spend our time and attention determines who we become. Once you’ve figured out who you want to be becoming, which direction you want to be changing in (we are always changing) the next question is, how will you set up your life to make that more likely? Work and education are all encompassing, taking up so much time and attention. It is not activity which we just get done so our “real lives” can happen elsewhere. Just look at the ways doctors or scientists or artists or teachers end up a lot like each other. They have been formed by what they have repeatedly done.

So perhaps you just need to pass an exam or complete a functional task. Maybe it is worth using tools to speed that up, because elsewhere in your life you are spending the freed up time and attention on stuff that will make you braver, or freer, more patient, more creative, excellent, just or kind, or whatever it is you are aiming for. This might be an example where using gen AI could align with your values.

This lovely piece in the New York Times (which I am hoping I have set up so you can read but it might not work in every country) is by an illustrator really wrestling with whether AI will kill his craft. He also says that he is already using the tools for functional tasks to enable him to focus more on the most human, impactful elements of his art making.

Perhaps this is how you are using it already. Tell me in the comments.

What kind of work is this?

Many of you have responded to my post seeking to differentiate between types of work. A reader working in tech, including AI products wrote:

I think there are meaningful distinctions to be drawn here between the use of writing to connect to other people (like yours does) and other uses of writing (computer code, business plans, financial accounts, etc) which are mainly used to interact with machines or other social systems. I value the first kind of writing for its own sake, and I wouldn't want to receive an AI-generated message from a loved one. But the other kinds of communication - like it or not, essential in the modern world - I only really value for what it achieves to help people.

When assessing whether to use gen AI or not, it is worth asking

If I did this task myself would I learn something, or grow in some way? Might tolerating the discomfort of it be healthy, or is it unnecessary and unproductive friction?

Does outsourcing this task to a machine risk decentering human creativity innovation or relationality (mine or others) or reducing other people’s ability to earn a living?

If I outsource this task, will I (honestly) use the time freed up to undertake activities in line with my values, which help me become and stay fully human?

Is the ease of outsourcing this task worth the extra energy cost? Where am I going to restrain my energy use to reflect this increase?

These questions may lead you towards hybrid approaches. The study of the cognitive effect of LLMs in essay writing I quoted above offered one possibility. They concluded that the use of LLMs resulted in much lower cognitive engagement (basically, was useless for learning or retaining anything), but writing the essay first and then using an LLM to improve it still allowed for some learning to happen.

What, therefore, are my boundaries?

My encouragement to you would be to figure out some of this stuff before using gen AI becomes a really entrenched habit. Work out what your boundaries are, and then crucially, get some accountability for those. Talk to other people about what you will and won’t do. Write it down. Commit in some way. Make it more than a vague intention which, I guarantee you, will crumble the first time it comes under pressure. Humans, including me, have an almost limitless capacity for self-justification and self-deception. Alone, we are pretty crap at living by our principles and values. We were designed, I believe, to be in morally formative communities with a shared vision of the human, a shared vision of the good. This is one of the things religions know how to do, and I’m not sure we’ve found a way to replace that. Whether you find it there or not, our best hope of living the kinds of meaningful lives of moral courage I think most of us long for is together. If you want to use the comments section as an accountability mechanism, speaking out loud what you are committing to, please go ahead. I’d love to learn from your reflections.

Upcoming events

I’m speaking again at The Realisation Festival in Dorset this Friday, 27th June, running a workshop on the changing spiritual landscape and interviewing former Sacred guest and all round force of nature

.In August I’ll be in Chicago at Midwestuary, alongside

, John Vervaeke and Jonathan Pageau, among others.

Lately, in a effort to remain a reasonably contemplative and connected human, I’ve been letting questions ‘hang’ around me, the way they used to before search engines. I simply don’t need to know the answer to every question I have, least of all right now. Sometimes just chewing on the question opens a door or leads me towards a paper book and the dedicated works of a human that spent a lifetime in a scholarly pursuit of a thing, whatever it is I find myself reading. I notice I’m really grateful for their dedication. I’m here for it.

As for AI… Well, I’ll never use it for my creative writing, that I’m clearly and lovingly committed to. Like all expeditious things, I fear that not all that glitters is gold, so I approach it with spacious caution, and will hold space for the natural world joyfully while others succumb to AI’s seductive offerings.

I’m just not in that big of a hurry, and perhaps my personal rebellion is to slow down even more. Rose smelling daily.

Another good one Elizabeth, AI kind of freaks me out, the only AI thing I use is spell check, hope you enjoy your time in Chicago, it's very nice.