5 reasons I’m AI Sober (and zoom book club today)

I’m pro-human, pro-humanities and pro-human relationships, so my values won’t let me use generative AI, right now. I’d love to hear your reflections.

Event today

Today, June 12th, 8pm-9.30pm BST I am hosting a zoom book club on Fully Alive to celebrate its paperback release. There will be time to meet other people, discuss which temptation to disconnection we feel most strongly about, ask some of the questions from the discussion guide and generally pool both our befuddlement and hard won wisdom.

You’re welcome if you’ve read the whole book, some of it, have a sense of what it’s about or just fancy a conversation about deep themes. No checking of homework! There will also be a chance to share from your own perspectives and experience but no pressure to. Introverts welcome.

If you are already a paying subscriber you will be able to see the zoom link at the bottom. Paying subscribers are a big reason I continue to be able to write, so thank you. Seriously. If you’re not, and would like to come, please consider upgrading for a month - it is just £5 - and if that is prohibitive drop me a message and I’ll happily comp you. I’d love everyone who wants to be there to be able to come.

I am not using generative AI. At all. I actually don’t know how rare this is, now, how rare it will become. Some of it is just head-in-the-sand, late adopter tendencies, and my age and stage. The philosophical underpinnings behind my aversion have been coming into focus recently though, and I’d love to hear what you think about them. Feel free to challenge and complicate this for me in the comments. It helps to think aloud, together.

I’m a Creative

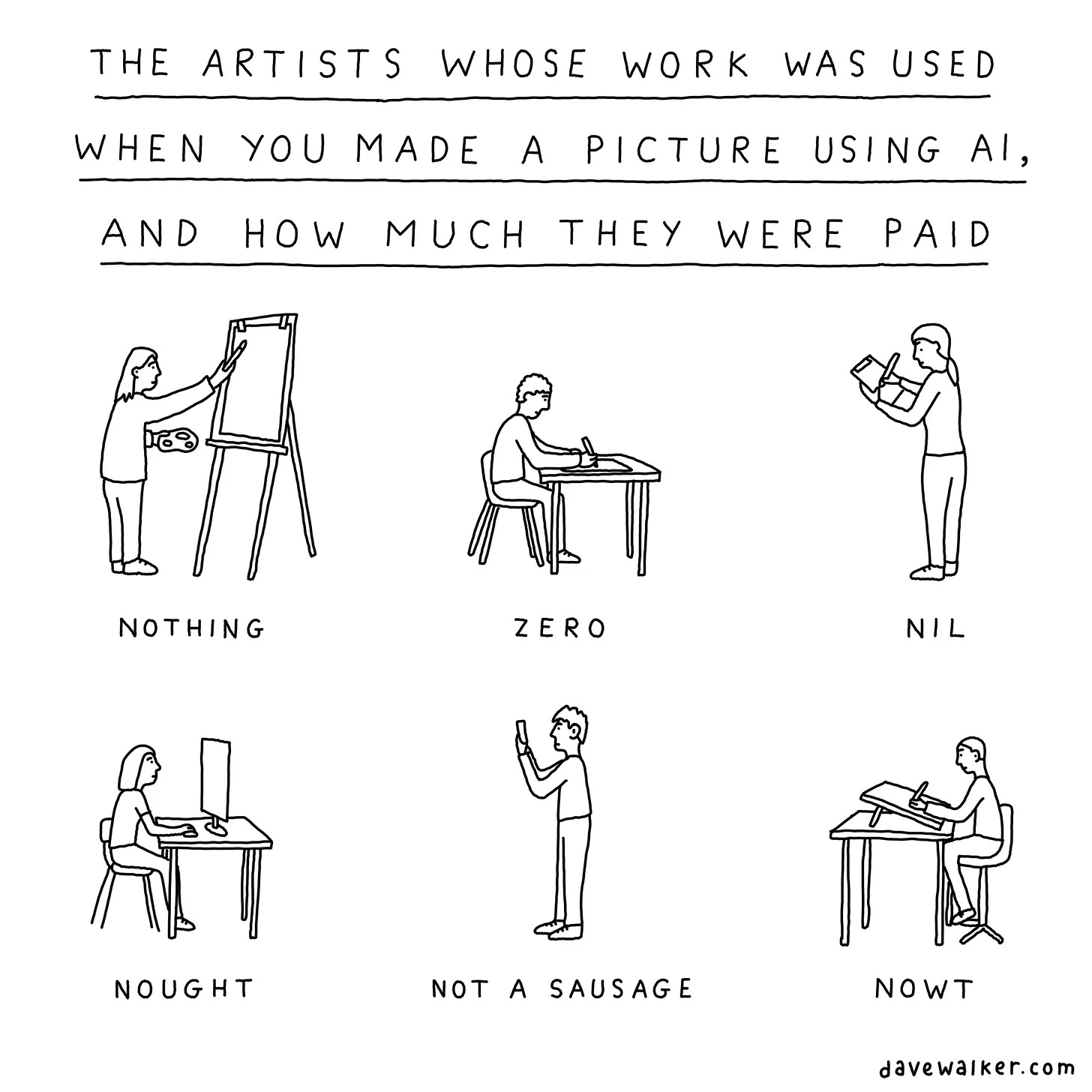

It has taken me a long time to feel comfortable calling myself a creative. Everyone is creative, or can be, of course, but for those of us trying to make our living through creative work, this moment is chilling. Whether you look at copyright issues, getting paid or just the straightforward amputation of creative humans from the systems that have (sort of) supported them, AI may well kill human creativity, or relegate it to hobby status.

The best case scenario seems that human creative work will end up as a luxury item where you can pay a premium for non-AI ‘craft content’ like ‘craft beer’. Small batch, no chemicals. It will be only available at expensive farmers market equivalents and consuming it signal cultural discernment. Everyone except the wealthy will have to make do with sloppy recycled stories, images and songs.

I do not want to be complicit in this.

I’m a Humanist

Being a humanist entails a concern for and defence of the human. Not as an expendable species we can evolve past, not as a virus or the scourge of the earth, but precious. It doesn’t mean we don’t care for the more-than-human world, or fail to reckon with our rapacious tendencies (this is why I find the concept of sin so helpful). It does mean a deep commitment to not, for example, participating in the self-erasure of human labour and self-atrophy of human intellect.

The word humanist has a bundle of complex associations. You might be most familiar with the term through secular humanism (I resisted the urge to put “so-called” in front of the secular there, because it sounds snarkier than I mean it, but let’s leave its ghost there for another essay). Humanism now is associated with atheism. This is a strange historical detour. Originally it was a term used about Erasmus, St Thomas More and other renaissance Catholic thinkers calling for reform of the Church. They were deeply influenced both by classical ideas and the way Jesus’ incarnation dignifies and affirms our enfleshed human existence. Bad sources will tell you that a concern with the human is and was somehow in opposition to “religion”, but that is bullshit. Probably all religions worth the name, and certainly Christianity, with its God-become-human, is unavoidably anthropocentric.

I recently took part in a conference at the Macdonald Centre for Theology, Ethics and Public Life on the topic of Christian Humanism and the Black Atlantic. It was a gathering of scholars wondering if Christian Humanism might again be a concept around which those who want to resist the dehumanising tides of our time can gather. Dehumanisation is everywhere: inside the church, in our politics, in our technology. The heart of Christian Humanism, scripturally, is the moment when Pontius Pilate points to Jesus, beaten, bloodied and about to be judicially executed and says “Ecce Homo”: Behold the human. It claims that true humanity is revealed not in power, “reason” or speed, but in this vulnerable, seemingly powerless figure.

Different scholars at the conference had slightly different definitions of modern Christian Humanism, but some shared themes emerged:

a belief in the dignity, equality and ends-not-means nature of all humans.

a focus on the relational nature of human beings, resisting individualism (this is where it crosses over with personalism, the founding doctrine of figures like Martin Luther King Jr.)

an emphasis on education, and particularly reading, as essential in becoming and staying fully human.

Generative AI in its current form seems a threat to all three of these, especially the second two.

I’d love to read humanistic responses to AI, whether Christian or otherwise. Can you help?

I’m lazy

I don’t love this term, but it’s true. It is probably true of all of us. Hedonic adaptation means that once we’ve got used to doing things the easy way, it’s almost impossible to return to doing things the harder, longer way. No one sends letters now we can email, and fewer people email now we can message, and messages are just 50% emojis. Has human communication evolved towards ever more richness and intimacy? It has not. As

laid out so brilliantly in 4000 Weeks, the promise of ever increasing speed and convenience is a mirage. The moment when we feel liberated, luxuriating in endless time and mental space while the robots do the grunt work is always just over the horizon. Each new tech that promises it, lies. The remaining work just expands to fill the gap that has opened up, or we spaff it meaninglessly away in numbed out “leisure” on the same screens we are otherwise working on.Generative AI seems especially dark in its promise of liberation. Industrial manufacture reduced craft skills, and household technologies reduced home-based hard labour, and at least in theory both of those offered more time for the things formal and implicit humanism have always promoted: education, culture, time with people we love, time in nature. Generative AI offers to do for us precisely the activities thoughtful humans long to have more time for, which feel most central to our humanity. It offers to replace the need to read, to write, to do that hard relational work of engaging with a friend, neighbour or counsellor.

Generative AI offers to harvest the best of us, ultra-process it and pump it back out at us in homogenised, de- humanised, frictionless form. It is a horrifying photo-negative of humanism.

I feel strongly because I so deeply understand the pull. I do not want to be uncomfortable. I do not want to be bored, or have that anxious buzz when I don’t know how to do something and I’m scared of being exposed. I do not want to have to go digging for the references for this piece, engage with a real artist to get the great cartoon at the top, and then pay for it, when an AI Butler would do it all for me. I know full well I could ask Claude to write this piece for me and then go back to bed. It sounds so, so convenient.

I am not going to go back to bed. Writing this piece is hard mental work, forcing me to think more clearly, express myself better. It is not relaxing or easy but it is meaningful. If I manage to make it any good I will experience the satisfaction of mastery, which is one of the things that makes work, even difficult work, enjoyable.

You can’t get to the enjoyment of mastery without first finding something difficult. Growing up is partly about learning to tolerate the discomfort of that. Discomfort in general, in fact. Nothing meaningful ever happens unless we do. Growing up a soul is also about discomfort, the kind of discomfort of stretching out beyond our tiny skull sized kingdoms into connection. It is risky and inconvenient and cannot be optimised. It is what we were made for, where Fully Aliveness happens. The only path to joy, which is deeper, richer, fuller and more glorious than mere pleasure or passing comfort.

I know there are no shortcuts to becoming a loving, wise, deep, patient, honest person. To becoming a writer with something to say, a person with something real to offer. Being clear-eyed about the temptation of laziness helps me see the seductive danger of shortcuts. I know that if I start using Chat-GPT, even for the small, functional tasks that make pragmatic sense, many of which I am sure you are already doing, where it doesn’t seem to immediately come into conflict with my values, I won’t stop. A day will come when I’m tired and have a deadline, and I’ll ask it to do something I have spent many years learning, and then those skills will sit on a shelf in my mind gathering dust in the back of my mind for the rest of my life. I will come up with some good reason why it’s fine. I do not have the self discipline to discern, every time, whether using these tools is wise. It is too much emotional energy. I am too skilled at self-deceit. For now, the boundary feels like protection, not constraint.

I’m a listener

I was really troubled to see this announcement. Kim Scott, who wrote Radical Candor, a very helpful book about feedback, has worked with Google to create a “portrait” of herself. On Instagram, she said this:

“Portraits is an experiment which lets you talk with me (well, an AI version of me) about communication, leadership and feedback. It is built with my voice, my thinking…I’ve always loved hearing from readers. But one of the hardest parts of my work is not being able to have every conversation I want to have. This project helps change that.

My son even tried it and said talking to the Portrait was more fun than talking to me! 😂”

Coaching is a word that is used for many different things, but at heart, it is a practice of deep listening. When I coach people it is a relational encounter. By creating a robust conversational container, good coaching helps a coachee hear themselves. Sure, sometimes it is functional, and the coach is simply a sounding board for project planning or sorting through options, but it rarely stays solely functional. Every decision we make, every tricky work conundrum connects umbilically to our deep values, the person we want to be, our vision of a good life. Listening to people at this level is sacred work. This obviously also applies, even more so, to therapists. Attention is a moral act, and a gift, and a form of intimate connection. I do not believe these things can be given by a non-human. They can be faked, sure. A simulation of attention can be offered by a simulation of a human, and it might scratch an itch, but it’s an illusion. Nothing relational has happened, because human listeners don’t always adapt to what they think we want to hear.

I understand Kim Scott’s reasoning. Of course she wants to help more people (for a fee). Our physical limits, our finitude, are a pain in the arse. Literally, sometimes. Limits, pain, the fleetingness of time: these are all key ways we are different from machines. Why would we want to become more like machines? Only if we have a stunted vision of the human does this seem like a good plan. And the last line is frankly chilling.

I remember reading Jean Baudrillard on signs and symbols, simulacra and simulation as an undergrad. Baudrillard was writing about the hyper real, the simulation by the media of human lives which act as a distraction from our actual lives. Now, generative AI has added another mind-bending layer to his hyper reality:

“The whole system becomes weightless, it is no longer anything but a gigantic simulacrum - not unreal, but simulacrum, that is to say never exchanged for the real, but exchanged for itself, in an uninterrupted circuit without reference or circumference1.”

I want the Real. The Really Real. The earth, and God, and other people. I do not want to have to learn to relate to machines which simulate humanity but cannot bleed, weep or be crucified. Which do not fart or laugh so hard they let out a little bit of wee. Relating to humans is hard and what we were made for. If we let ourselves off the hook with these simulated relationships we will never experience the fullness of life but be trapped forever in a terrifying self-referential hall of mirrors. I refuse. If it makes me less efficient, less profitable, a left behind dinosaur, so be it.

I love a boundary

Very few ethical issues are black and white. I’m old enough to know that living my values is complex, that I often change my mind. I am choosing to be dogmatic about AI at the moment because I don’t want to get swept along with the tide of something I can’t extricate myself from, and because habits and practices are central to formation. I have come to believe, though I am not temperamentally inclined towards them, that boundaries about what we will and won’t do makes becoming the people we want to be easier.

For five years I didn’t fly for climate reasons, and it was a relief not to have to decide. Then a family member moved to the US and flying seemed justifiable, then I started getting offered meaningful (and financially helpful) work abroad. Now my boundary is just “no flying unless for work or family” and I find myself flying a lot. I don’t know that I can have a better policy right now, but I am still conflicted. More positively, in our community house we have committed to get up early three days a week to pray together in our chapel. I hate it, every time the alarm goes off, but I have never regretted it. That past commitment is a present from my past self, and it holds me into a practice I in theory want but struggle to choose in the moment. Writing this post is, if I’m honest, an attempt to hold my future self into these intuitions. It’s my own personal public twelve step commitment. Feel free to join my club. Your boundary might be different from mine, if you have stronger self-discipline than me (I’ll use it for x not x), but I’d encourage you to ask the questions about your values and how this all aligns.

Writing this piece might also remind me of the risk on the days when it all seems so tempting. Changing your mind in public is mildly embarrassing (though sometimes necessary), and if there is a reason good enough to reach that threshold it might just be a good enough reason. I guess there is a challenge for you, in the comments.

This is from Simulacra and Simulation, and I got it from a list of Good Reads quotes because it turns out I gave away my undergraduate copy. That was shortsighted. Also the first part of that paragraph is about God, and whether you can simulate God, which is intriguing. I don’t have the page number. Maybe I should ask Claude to find it for me. Meanwhile, if you’re interested in this rabbit hole, this is a helpful article: https://www.iacis.org/iis/2024/2_iis_2024_1-8.pdf

So glad you wrote this. I appreciate you, human Elizabeth, doing the hard work to clearly articulate what I’ve been thinking.

I am in the zero-acceptance category myself, writing back and forth with my grandchildren (stamps! handwriting!), lugging a Thesaurus to my writing desk, asking folks not to send AI note takers to Zoom meetings (vs attending personally). I’m holding out for the spaces where we meet each other in messy reality.

I eschew parking aids in my car for fear my confidence and spatial awareness will atrophy. I use paper maps when I can so I understand the location of one place relative to another. I buy original art or decorate with found objects.

I’m holding out with you!

Thanks for rescuing humanism, the term that is.

With regard to mechanised intelligence I offer two books by Jeremy Naydler. I initially entered substack in order to write reviews of them. I had been fortunate that a friend had personal contact with Naydler. The reviews were posted at the start but I have pinned 'The Struggle for a Human Future'. His earlier book of the two, 'In the Shadow of the Machine' is by the way an excellent history of the long intellectual evolution from antiquity with wonderfully chosen illustrations.

My inevitably modern mind struggled a bit but I learned a great deal. There are mundane reasons for not boarding the AI boat, but as you suggest it is a trap for frail humans like me and you. You can read my two pen'th worth. Mark Vernon had a review much earlier in the Church Times for 'Shadow of the Machine'.