Trains, planes and automobiles

How travel forms us, featuring Muriel Spark, Thomas Hardy, Andy Crouch and Wall-E

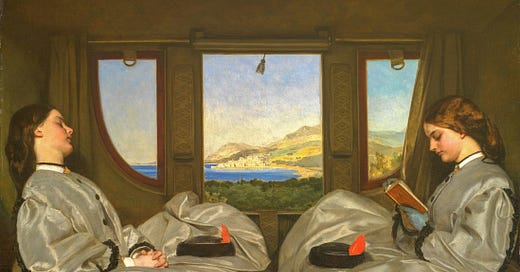

I have spent part of the summer crisscrossing Europe on trains. That is me on the left. Chunks of my twenties unfolded while interrailing, including a memorable trip overland from Manchester to Istanbul, which I decided was the appropriate response to a broken heart (I was right). I am the daughter of a train spotter, and despite mocking him throughout my childhood and bemoaning the hours spent on steam engines, I get it. I love the sound and the sway of rail travel, the romance of it. Stations of glass and steel arching upwards like cathedrals inspire something close to awe in me. Clearly, the most noble form of transport is the bicycle, but a train comes a close second.

This year, we decided our kids were old enough to tolerate the long periods of sitting down, and so I was able to rekindle my love affair. We set off the slow way to stay with friends in Sweden with a suitcase of books, games, audio book CDs and old-school discmans.

One of the main joys of train travel is people watching. As we passed through three countries in a day I observed the social mores changing slightly, levels of brusqueness rising and falling. I also saw, repeatedly, humans at their least guarded. There is something about travel amongst those we will never see again that means we cease to perform. Muriel Spark describes the vulnerability of people asleep on trains, the curious intimacy of being observed in this usually private act:

“…a row of people opposite me, dozing untidily with heads askew, and, as it often seems with sleeping strangers, their features had assumed extra emphasis and individuality, sometimes disturbing to watch. It was if they had rendered up their daytime talent for obliterating the outward traces of themselves in exchange for mental obliteration. In this way they resembled a twelfth century fresco; there was a look of medieval unselfconsciousness about the[m]”.

This undefendedness also showed up as we tried to navigate the multiple complex ticketing systems which sometimes failed to tesselate. A train is delayed and passengers rush the guard, faces tight, to learn their fate. Will I make my connection? Can I get my money back? We look things up for each other, translating information as best we can, relishing the solidarity of a shared eye roll. No one is cool in these moments. The confrontation with powerful systems, the seeking of mercy from the human face representing them, strips us all bare. I felt a fierce tenderness for my fellow passengers, pilgrims all, tossed on the waves of European rail stock.

They - we - are not beautiful in these unselfconscious moments, in any normal sense. More often we are harassed and twitchy or slack jawed in repose. But we are open, and I find that openness beautiful1.

A few weeks later, we were back in the UK and travelling long distances by car to visit grandparents, patching together enough holiday childcare to allow us both to work. I’m grateful to have a car - we didn’t for a long time, until gifted one anonymously by someone at our church - but I see no romance in the open road. Maybe it’s living in a traffic choked city, maybe the fact that 50% of our family have chronic travel sickness, maybe the complicity cars require in our kamikaze-carbon economy2.

Recently, we’d pulled over at a service station for a wee and a break from a long tailback. The traffic chaos was affecting everyone there, but no solidarity resulted. We were not open. There were too few parking spaces in the unending field of hot, shining metal, so it was every driver for themselves, soundtracked by a discordant symphony of honking. Once parked and disgorged from our stale-aired tins, no one made eye contact with anyone else, the crowds simply hurdles in our individual quests for relief and refreshment. I stood waiting for my kids in the airplane-hanger sized space, occasionally jostled by the queues for the automated McDonalds ordering screens, and had a moment of profound revulsion. All I could see was neon signs and adverts. Everywhere smelled of frying oil and artificial air freshener. The same sodding “breakthrough pop hit of the summer” simpered over a bass line of tearing plastic packaging. Moments of connection with my follow travellers felt not just unlikely but actively unwanted. Ugh. Not them. Come on Liz, I said to myself, stop being such a superior snob. You’re not King Charles. It may not be beautiful but it’s convenient. I went back to our car trying to shake off the vision of hell by side of the M3.

It left me wondering why I sense that rail travel is humanising, or at least less dehumanising, than car travel? Why did tenderness come easier to me on the tracks? It is entirely possible it’s just preference. I like old things, so the older transport must be better. I lean social democratic, not libertarian. It may just be a set of unconscious aesthetic and cultural associations. De gustibus non est disputandum. About matters of taste, there is no point arguing.

Maybe. Or maybe it is tugging on my deep values. I believe that all of life is formation. Everything we pay attention to, every place we repeatedly find ourselves shapes us. Even our transport. These subtle shifts in how humans interact with each other, in how I feel about them, seemed to be telling me something.

To decide if something is humanising or dehumanising it helps to surface our own working model of what a human is. I broadly agree with Andy Crouch that we are “heart-soul-mind-strength complexes designed for love”. He argues in The Life we are Looking For that we become more fully human when we are developing one or more of those faculties; deepening our emotional life, stretching our intellect, growing up our souls or using our physical strength, and especially when those things are in service of close relationship. Like me, Crouch is interested in formation, and specifically in the ways our technologies (including our transport) form us towards, or away from, our humanity.

Andy makes a distinction between two types of technology: tools and devices:

What separates tools from devices can be stated plainly: tools require and reward human involvement, while devices bypass and replace it. Human beings use tools, and tools are used by human beings. But devices are distinguished by the fact that as they progress, they require less and less human involvement to operate….

The big difference is that as tools improve and advance, human skill also improves and advances. But as devices improve and advance, human skill becomes less and less required, to the point of atrophy3.

When our technologies don’t encourage us to grow in our human gifts, but instead remove the need for them, we are designing our selves out of the picture. Devices satisfy our deep, ancient longing to be something more than what we are, for “magic”. Andy calls this “Superpower Zone” and it promises mastery without effort and abundance without dependence. It requires nothing of us, and removes (or hides) our reliance on others.

Superpower Zone sounds great. Of course we want more comfort, convenience, status and speed. Who doesn’t? Andy’s work has made me see that these things can be temptations to become less than fully human.

The root of the word travel is the old French travail, work or labour. We used to have to earn our relocations, use our minds rather than GPS to navigate, our bodies to walk or ride or cycle. We often worked together and depended on each other. As our transportation technologies develop, they move closer and closer to the Flying Car dream - fully autonomous, effortless, personalised transport, requiring no effort and no interaction with the annoyances other people present. Beyond that, you get the humans in Wall-E:

Crouch’s tool vs device framing has made me realise my instinctive preference for train over car travel is mainly just taste. Both are closer to devices than tools. The most humanising forms of transport (and this, I think, is why they remain most joyful, least likely to leave us feeling like a husk on arrival) are still the ones that ask something of us - cycling, running, walking as pilgrims in a group. Train travel is just slightly less far into Superpower Zone than cars. It doesn’t ask a lot of us, but it does leave us needing to stay alert to schedules and timing rather than outsourcing all the thinking. Perhaps most importantly for my values, we are forced up close to other people in all our vulnerable embodiment, as we sleep and eat and ask for help to get places. Even fleetingly, our risks are shared4. In our cars we are isolated, protected and (feel, at least) in control. When we emerge, stiff and blinking into a crowded service station, of course other humans look not like walking worlds of meaning, icons of the divine, but obstacles in the way of our goals.

This is not an argument that we should, or of course could, cancel cars. I have no desire to revert to a world of horses and carriages, not least because I probably would have died in childbirth and might have had to wear the same enormous skirts as the two women in the painting above. It is simply a reminder to myself to keep being aware of who I am becoming, not buy the lie that a good life is one that asks the least of me. To choose, when it’s practicable and plausible, a tool over a device, my bike over the car. Effort over magic, interdependence over autonomy. Growing in my heart, mind, soul and strength, not atrophying into one of the humans of Wall-E. Please can someone hide my car keys?

Just because it is beautiful, and because I like to imagine this “journeying boy” sitting a few carriages away from the grand ladies in the painting which accompanies this post, let’s finish with a train themed poem:

Midnight on the Great Western

In the third-class sat the journeying boy,

And the roof-lamp’s oily flame

Played down on his listless form and face,

Bewrapt past knowing to what he was going,

Or whence he came.

In the band of his hat the journeying boy

Had a ticket stuck; and a string

Around his neck bore the key of his box,

That twinkled gleams of the lamp’s sad beams

Like a living thing.

What past can be yours, O journeying boy,

Towards a world unknown,

Who calmly, as if incurious quite

On all at stake, can undertake

This plunge alone?

Knows your soul a sphere, O journeying boy,

Our rude realms far above,

Whence with spacious vision you mark and mete

This region of sin that you find you in

But are not of?

Thomas Hardy (1840–1928)

I feel a similar fierce tenderness toward my pre-teen children’s as yet intact unselfconsciousness. I know self-awareness will come, and with it performing for other people’s expectations. For now I allow my heart to break at the beauty of a child sitting chatting merrily to me through an open toilet door while doing a poo. Am I the only weirdo parent which finds this beautiful?

Living without a car with two young kids felt like a bridge too far, but writing this post has made me realise that now they are fully ambulant and require less kit, we could give it a go again.

https://journal.praxislabs.org/we-dont-need-superpowers-we-need-instruments-860459cfc165

Which is why trains are such great settings for golden age detective stories, another totally irrational reason I love them.

I’ll never forget a train ride in Italy back in 1978 when I went on my first trip to Europe from the US with my sister, cousin, aunt, and uncle. We spent five weeks traveling to see various relatives and on one long train trip from Rome to Florence, the five of us were sitting in a compartment with a stranger. It was one of those small compartments in a corridor coach where you have three seats directly facing another three seats. After a couple of hours, the stranger pulled out his packed lunch which looked like a bit of bread and cheese and awkwardly looked at all of us offering to share what he had. Though he had precious little to share, it was clear that he couldn’t bring himself to eat in front of us unless he had first invited us to eat with him.

I only joined your posts a week ago and already I am delighted! Thank you! I am a huge fan of trains (and steam trains) and the ability to slow down from crazy pace of life. Your point about community is also an interesting insight too.

You definitely made me smile regarding pre-teen consciousness - my son is 12 so just on the cusp of the shifts which happen and my husband and I love the moments when the child still shows - precious and to be savoured as much as possible (even if a little unsavoury at the time!!)

'Don't wish it past,

Don't speed on by,

For one day you will wonder why

You didn't dance amid the waves

And really make that moment last'