“I find the soul a valuable concept, a statement of the dignity of a human life and of the unutterable gravity of human action and experience….I find my own soul interesting company”.

Marilynne Robinson

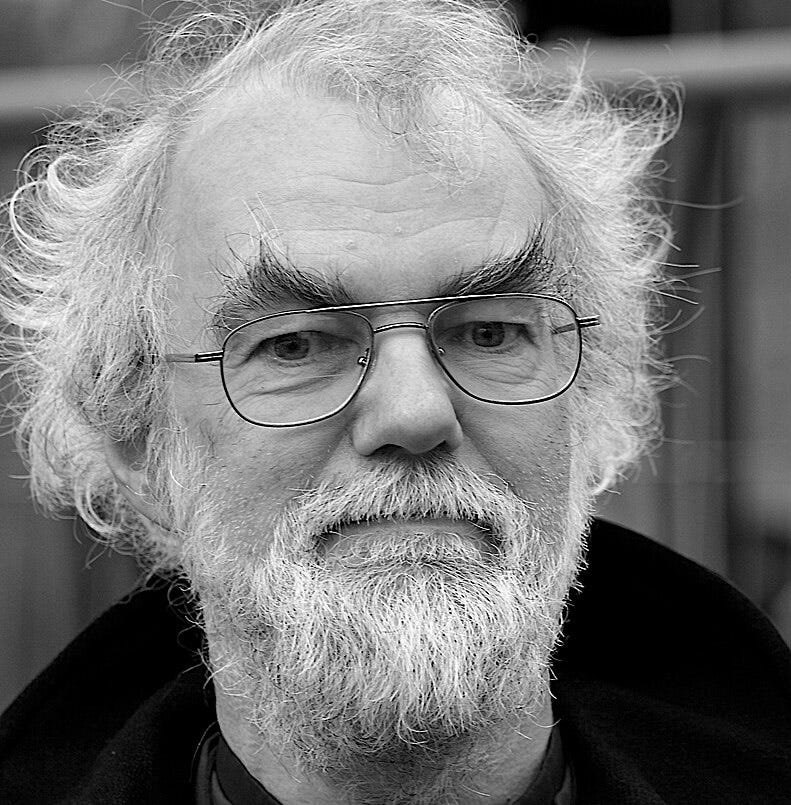

I have been reading Rowan Williams. I often am. Not in a scholarly way (much of his theology is too dense for me) but because whatever I am pondering, he will have said something wise about it. I had to ration my Rowan quotes (he is always Rowan, not Williams in my head) in Fully Alive. Maybe it’s because he is a poet as well as a theologian, maybe because he took on the costly and thankless task of institutional leadership, maybe it’s just the accent and the eyebrows, but I love him. I love his mind, and the way his mind does not appear to be separate from his character, something uncommon in Big Thinkers.

His recent book The Passions of the Soul is the most refreshing I have read in years, and connects to Fully Alive because we are both mining the tradition popularly known as the Seven Deadly Sins. It has been causing me to chew on what I mean by soul, and why I believe in tending to it, when in general I am nervous about an excessive interest in selves.

My anti-individualistic intuitions are strong. I believe in most situations there is too much emphasis on the I and not enough on the we. I want to resist the cultural formation that says the answer lies within me. It must, surely, be more relational than that. Augustine and Luther both use the Latin phrase homo incurvatus in se (man turned in on himself) to define sin, and that sounds right to me. When in doubt, don’t turn in, stretch out.

And yet. Disconnection with our own soul is one of the forms of fracture that both Rowan and I think is harming us. Our tendency to stuffocate our souls through accumulation (avarice) and numb them with addictive behaviours (gluttony) are barriers to Fully Aliveness. I have found becoming more aware of these tendencies in myself helpful. The Passions of the Soul explores this balance:

“It’s important to be honest about what’s in our minds, and…we need to be very aware of the ways in which we can slip from that honesty into a rather corrupting fascination with ourselves…[wisdom] involves walking a bit of a knife-edge between obsessive self-analysis and bland unawareness”.

The spiritual path which Rowan is unpacking in the book is about how to find our balance on this knife edge, to resist the self-obsessed orientation of so much of our culture in favour of something subtler. He is offering the:

“Eastern Christian approach to a certain kind of growth in self-awareness -what the texts themselves call ‘wakefulness’ - as a preliminary in the process of giving oneself to God in silence and loving God’s creation in humility and truthfulness.”

A wakefulness to our soul as a necessary first step in relationship with divine Love and creation also sounds right. But what am I waking up to?

Beside Rowan, I’ve been reading Changing my Mind by Zadie Smith, which is *amazing* and which I picked up from one the of the Little Free Libraries which are on every block in Washington D.C1. Very dangerous for someone travelling with only a carry on. Zadie (Smith also sounds wrong) is another imaginary friend. They would both be at my fantasy dinner party. More honest to say they both are at the dinner party which is often taking place in my head. They are bright stars in the constellation of my intellectual patron saints. [I wonder who yours are? Will you tell me in the comments?] Writing about ‘soulfulness’ in the novels of Zora Neale Hurston, she says:

“The dictionary has it this way: ‘expressing or appearing to express deep and often sorrowful feeling’. The culturally black meaning adds several more shades of colour. First shade: soulfulness is sorrowful feeling transformed into something beautiful, creative and self-renewing, and - as it reaches a pitch - ecstatic.”

This sense vibrated in the air as I walked around the National Museum of African American History this week. Galleries on slavery gave way to galleries about black music and culture. The soulfulness of Nina Simone singing is an alchemy, transubstantiating the agonies of black bodies into something beautiful, in ways that do not veil truth but instead help me hear it. It woke up something in me (my soul?) to reality.

This connects with the Eastern Christian tradition that Rowan is drawing on. It teaches that we must master the “passions” (by which they mean temptations) in order to increasingly inhabit an “angelic” or perhaps soulful way of seeing. Leaning over my dinner table and topping up Zadie’s wine glass, he defines this as:

“Seeing things just as they are, just as they emerge from the hand of God, we might say - an almost Zen-like clarity, perceiving the world in it’s simple thereness, resting on nothing but the creative act of God, glowing in its reality. The diabolical way of seeing the world is the opposite - the world of a kind of supermarket consumerism in which we experience and assess what is around us simply in terms of its profitability to us, as if it had no meaning except what our wants and fantasies projected on to it….the authentic human life is one always extending out beyond itself towards the clarity and spaciousness of vision that God wants for us”.

Maybe my soul is what sees clearly, and because reality is inescapably relational, it can’t help but point me outwards.

Zadie Smith’s second element of soulfulness:

“Another shade: to be soulful is to follow and fall in line with a feeling, to go where it takes you and not to go against its grain.”

I don’t think all feelings are worth following (some, Rowan would argue, are passions which need resisting), but many are. Maybe soulfulness requires us to align with the part of ourselves which will guide us aright. Not to stifle or shame our longing for relationship, to see and be seen, but to go where it takes us.

The capacity for navigating like this, Rowan writes, is known in the tradition as nous. This Greek word is sometimes translated as intellect, but is largely unmoored from our Oxbridge debating society, left-hemispheric narrowing of that word. Instead nous is

“The ‘instinct’ in us for seeing and loving what’s real and what’s true; a taste for the real, a kind of magnetic turning towards the real. And this means that nous is that capacity at the very centre of our being for turning Godwards, since God is what is unconditionally real….Nous then is the capacity for contemplation, the capacity for seeing, loving, absorbing, being transformed by what is supremely real.”

He summarises the spiritual path that he is describing as a way of learning “the skills of living in a way that is faithful to what we most deeply are”.

What we most deeply are. I think that is my definition of soul.

I am never going to land on a tight definition of it, but my mental dinner party with Zadie and Rowan has helped give me language for my working hunch. My soul is what I am most deeply am, the part that sees truly, and yet is not afraid. It is the me that knows my interdependence, does not need to be defended, loves and is loved. My self/flesh/shadow/sin does not know those things. Those parts of me need meeting with compassion, but they don’t get to steer. We’d only end up stuck, facing inwards. In waking to my soul, following where it leads me, I should also be increasingly awake to the world. I don’t know if the eyebrows just come along with the process, but I can hope.

Before this all starts sounding too high brown I am also reading Magpie Murders by Anthony Horowitz and watching Bridgetown because I believe in a balanced diet.

A couple of fantasy dinner party (or bbq) guests...

First, George MacDonald. Just read (and highlighted almost all of) C S Lewis's anthology of his nuggets. Very fresh. Interesting to see the same kind of insights about soul and self that Rowan draws from Eastern Christianity, and a McGilchrist-like explanation of the value of attention, from a nineteenth century Scottish Congregationalist.

And Australian writer, Tim Winton. Apart from being befriended by his novels, I came across his short piece, Twice on Sundays, in the collection of autobiographical essays, The Boy Behind the Curtain. A lovely, clear-eyed, and honest account of Evangelical churchgoing as a child, teenager, and young adult, and trying (then not-trying) to articulate what being a practicing Christian has meant to him in later life. A bit of tonic in the deconstructing-faith genre. Like MacDonald, homely and in-his-skin, but marked by encounters with grace.

Great stuff!

As often happens, I hear a lot of resonances with Piranesi by Susanna Clarke (a guest at my intellectual dinner party!), in the way that [minor spoilers] Piranesi is able to perceive the world around him 'in its simple thereness, resting on nothing but the creative act of God, glowing in its reality'; a contrast to The Other, who is blinded by avarice and cannot see beyond the projection of his own wants and fantasies.

There is also soulfulness in the way he transforms his pain and confinement into something 'beautiful, creative and self-renewing', and such bittersweetness in his tending to the remains of the people he has found, trying to form relationships and community in the most arid conditions.

I hope/suspect you've read it, but thank you for shedding light on one of my favs either way! A very 'fully alive' kind of book I think.