What about Carl? When transactions are required.

A Relationshipaholic in recovery (Relationships series Part 4)

My name is Elizabeth Oldfield, and I am a relationshipaholic.

About 18 months ago our little intentional community were attempting to move house. We’d started renting together during the pandemic, after a year of careful conversations, visiting other communities, planning and prayer. What had started as an impossible seeming dream (space for one family in London is expensive enough, let alone two with room for guests) was slowly, inch by inch becoming a reality. We’d been able to afford to rent together because some dear friends of ours had left London during lockdown and were able to offer us their house at “mates rates”. Even then, we were living way beyond our means, and having achieved the aim of confirming we could actually live together, were keen to move on. Because of the generosity of a group of people willing to back the vision, and an organisation willing to hold their investments and undertake a form of shared ownership with us, we were suddenly in a position to buy something.

Lining up the logistics of a house move is stressful under the best circumstances. We’d found extra barriers at every step of the process, because we don’t fit the boxes the systems are expecting. Very few banks will give a mortgage to four adults, even fewer those buying via shared ownership. Estate agents are suspicious, sellers worried their neighbours will hate them if they turn out to have sold to a cult. Even in our privileged, complex and hard won position, we kept getting outbid.

When we finally had an offer accepted, the estate agent asked if he could put the sellers in touch directly. They wanted to explain the back story to something (knotweed, as it happened). An alarm bell rang in my head, half-remembered stories of difficult sellers, but to say no seemed anti-relational. Real, human contact is always the better idea, I reasoned. Fewer chances for misunderstandings.

I was wrong. My dogged commitment to relationships over transactions meant a seller who had seemingly never sold or bought a property before had a direct line to me. They was finding the whole process emotional, and apparently I was the right person to vent this on. They kept changing their minds, going away for months at a time, finding our solicitors entirely standard requests for paperwork intrusive and overwhelming. As time passed they got increasingly belligerent and repeatedly threatened to pull out of the purchase. We’d already had to give notice on our rental property to avoid causing problems for our friends, and so ending up without somewhere to live began to be a real possibility (this did, in the end, come to pass and we slept on friends sofas and spare rooms for three months). I began to get a fight-or-flight threat reaction whenever I saw a message or email from them. As the chain above them began to buckle, at one point they suggested they rent us part of the house and stay in the other part, and my response was ice cold fear at the idea of close proximity. I’d rather be homeless, I thought.

At the same time, we were trying to honour the friends who we’d rented from, who needed to find their next tenants. They’d been so kind to us I was keen to make sure they didn’t end up out of pocket because of our purchase chaos, so I volunteered to liaise with their estate agent. He was called Carl and in his early twenties. With his slicked back hair, clipboard and shiny high street suit he was straight from central casting. And yet. He was a person, so I needed to have a relationship with him. I asked him my usual curious questions, made him tea, tried to connect. He seemed mainly bemused and carried on with his standard, scripted patter.

All this came to a head in a week when I’d been fielding calls from our unstable sellers, packing to leave the rental not knowing where we were going and holding our fragile chain together through sheer force of will. It meant I needed to cancel a visit from Carl, but I couldn’t. It didn’t seem right to mess him about. I was frantic at our weekly house night, explaining all these relational threads I was desperately clutching, and ending up crying hysterically “What about Carl? None of this is his fault?”.

“What about Carl?” has become my mental shorthand for my tendency to take relationality too far. I was completely strung out trying to move house in a relational way, in a system designed for the opposite. My housemates gently suggested that Carl would probably be ok, that I maybe I didn’t need an I-thou relationship with our friends estate agent on top of everything else. They pointed out it was possible he was used to a bit disruption, and didn’t take it personally, and frankly, his feelings weren’t my responsibility anyway. They also offered to take over contact with our seller, or indeed get our own estate agent to do it, as is usual.

I remember the bodily relief I felt. Living in community is a short cut to noticing unhelpful patterns in yourself, and mine had been treated with such care. Trying to stay loyal to my sacred value of relationships had nearly been the straw that broke my mental health in an already difficult time. Permission to be selective was liberating.

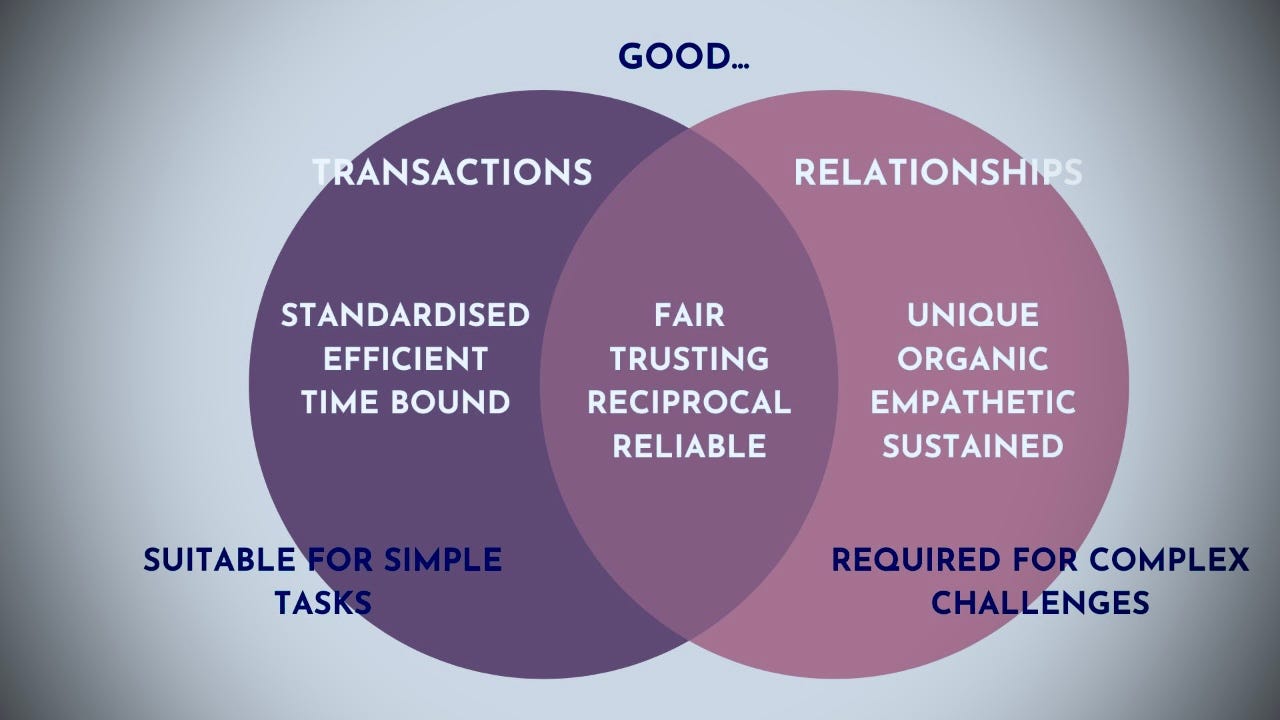

Since then, I’ve been trying to be more boundaried, to get over my allergy to transactional human encounters and relax about them. Working with The Relationships Project has helped with this, because they are very clear that sometimes transactions are exactly what is called for.

They argue that

There is the difference between a relationship and a transaction. One is not intrinsically preferable to the other. It all depends on the context. For example, I have a relationship with my son. My association with the rail company from whom I bought a ticket is purely transactional. [T]here is nothing inevitably bad about a transaction. If the ticket is supplied promptly and fairly it was a reciprocal exchange and a good transaction.

I had accrued a set of associations with transactions which were not serving me. I thought anything less than deep human-to-human contact was somehow dehumanising, but it isn’t. I could still treat Carl with respect and fairness, and he me, while not adding to my emotional load.

Two years later, I’m a work in progress. Recently I got three quotes for tree surgeons, and because I’d had a lovely chat with Eileen at the office felt compelled to go with her company. My harder-headed housemates suggested we go with the cheaper, better reviewed one, and even though part of me cried “What about Eileen?!” I was able to let it go (I prayed a little blessing for her, which helped).

Writing this has made me realise all the things we hold sacred probably have a shadow side. Some guests on my podcast reject the premise of the question for precisely that reason - sacred or deep values to them mean something that can’t change or flex, and that is dangerous. I am interested in when our deep values are a lamp to our feet, a compass for the life we want to live, and where they might blind us to other goods, other goals. I’m interested in how this shows up for you. Please do let me know in the comments what you are learning about your deepest values, and if you think they, too, might sometimes need a limit.

Photo by cotton bro studio on pexels.

"maybe I didn’t need an I-thou relationship with our friends estate agent on top of everything else"

ROARED with laughter! My lands, that is rich and diagnostic.

And this: "Writing this has made me realise all the things we hold sacred probably have a shadow side" - BAM.

Briliant.

What a tremendous post, Elizabeth! Thank you.

Someone I know very nearly bought a house he knew wasn’t right for him because he was gripped by the feeling that he’d be letting down the vendors, somehow breaching the ethics of relationship, despite barely knowing them. I had to talk him out of it by emphasising that he was in a transaction not a relationship. Your post speaks to this…Of course transaction and relationship intertwine, and as they do so, then ethical questions and challenges do arise. But I think they don’t when there is a) no harm being done to anyone and b) there is no prospect of continuing interaction, which of course requires the fostering and boundary-setting of relationship.

In the Christian life we can feel that imitation of Christ - an impossible demand, while also a necessary one - means extending care and love of neighbour to everyone all the time. But we can’t. God can, but not us. We are embodied creatures with limits of physicality and energy and capability. Not every situation can be met with the same commitment of care, and trying to do so will deplete us. We have to be able to discern ethical demand from ordinary (but humanly responsible) transaction. That may not be easy - I speak as a non-expert! - and will always be work-in-progress. But we can’t make the exhaustive effort to be Christlike if we are already exhausted by trying to relate when all we need to do is transact (nicely).