On knowing my own precarity

Fear, wealth and giving thanks for a human called Joquone.

I have had a very strange week. I am stuck in Denver, with whiplash from starting my day in one world and ending it in another.

I had not planned to be here. I received a last minute invite to speak at Aspen Ideas, in Colorado, and figured I could just about squeeze it in between other book events. I had only vaguely heard of the festival, but it turns out it’s a Big Deal in the US, a sort of Davos x Coachella x Ted. Tickets cost $5,000 for four days (not including accommodation) and world leaders and celebrities hang out in the mountains promoting their books and putting the world to rights. Everyone is intimidatingly glamorous.

I don’t mean to sound dismissive - the Aspen Institute in general seems to be doing important work and asking the right questions, and there were cohorts of young people there on access schemes. It was an amazing oppurtunity, only possible through the tireless championing of my amazing friend Anne Snyder, who is editor of Comment magazine. It just isn’t a world I feel at home in. I spent much of it bottling opportunities to network and instead escaping to the surrounding, astonishing mountains, photographing wildflowers and putting my feet in the rushing snow melt river.

The bits that did connect did so deeply - intense conversations with old friends like Anne and new ones, including

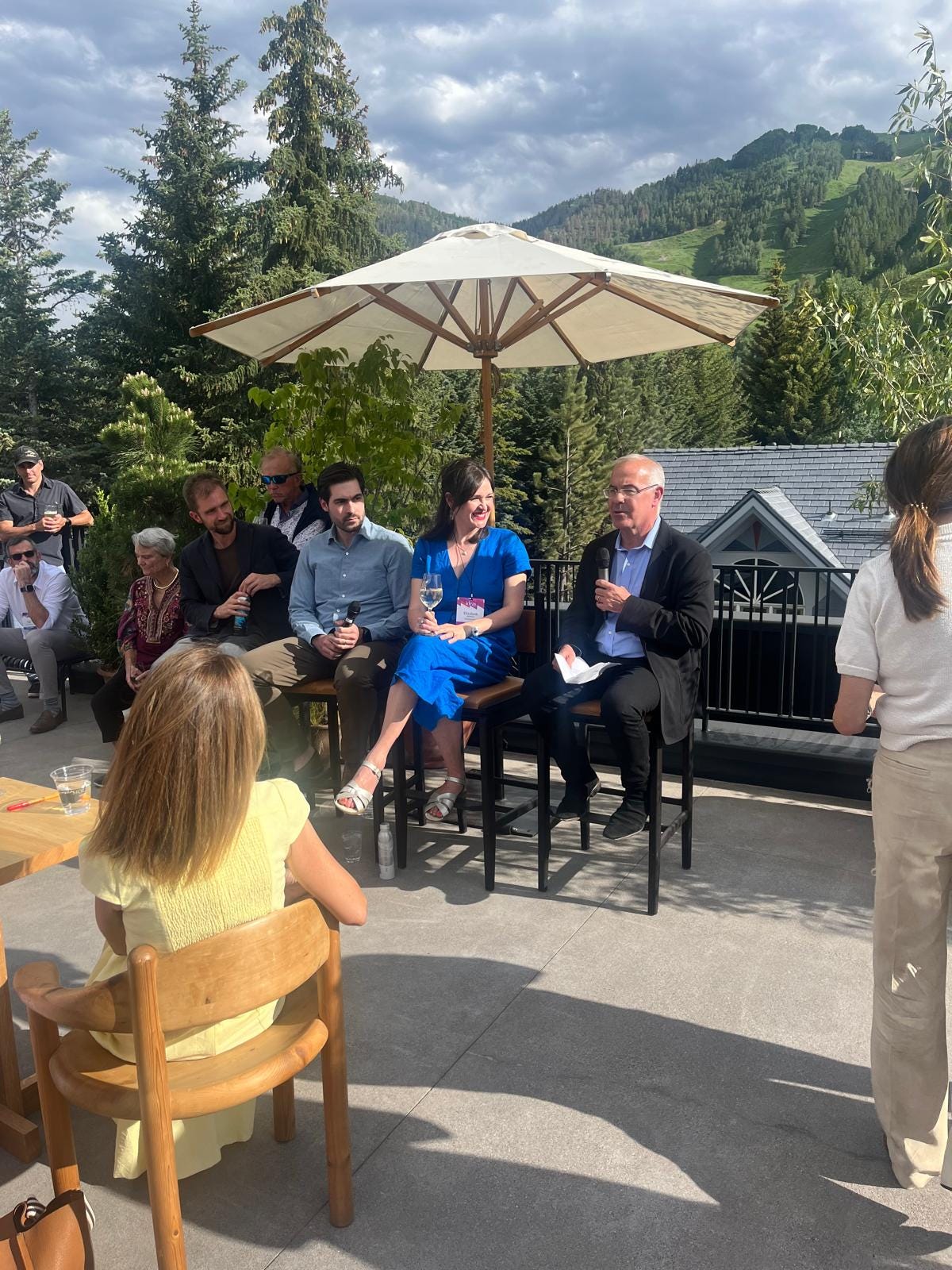

. I would highly recommend his book on Friendship as Sacred Knowing if you are philosophically inclined. (The Sacred episode I recorded with him is forthcoming). We spoke about vulnerability as the necessary condition for intimacy, for interdependence, for being fully human. I got to touch on the theme again in a wonderful panel event I did with Samuel, David Brooks and Agustín Coppel Gomez, in front of an audience many of whose wealth and influence makes vulnerability and interdependence a complicated prospect. In the book signing line afterwards, the loneliness of this group was evident. There were some tears, several hugs, and one woman said “it is such a joy to talk about these existential things with someone other than my therapist”. Behind the gloss and glitz they were real fragile complex humans, longing for connection. Of course they were. How could they not be? I felt chastened in my prejudices.So vulnerability was on my mind, but very much not in my surroundings. On the last day I breakfasted on chia peanut butter pudding and organic non-GMO zucchini bread with two New York Times columnists and a legendary magazine editor. On the next table, David Milliband was chatting with Katie Couric. Then I filled the free backpack with free food and headed for the airport, homeward bound.

That is when things started to unravel. Aspen airport is tiny and treacherous, only approachable from one direction through the high passes, when the wind blows in a specific direction. Storms in Aspen and Denver grounded us, and I missed one London connection, then another. At 10pm I reached Denver, and was told there were no flights until the following morning. The airline would not help with accommodation (weather), and told me that most of the hotels in Denver were fully booked because of the the storms.

Fine, I thought. I can do this. I backpacked a lot in my twenties, in central and eastern Europe and New Zealand, India, parts of Africa. I’d found my way through less safe cities than Denver on just my charm, chutzpah and a battered Lonely Planet. Everything is figureoutable. I may now be a middle aged mother, injecting adventure into her life in more local ways, but surely those skills were still in there.

Two hours later, I was flagging. I’d found a reservation, I thought, and attempted to get the bus there, but the ticket machine wouldn’t accept my cards, so I shelled out on an extortionate Uber only to find when I arrived that the hotel was full. So were the other faceless chains clustered together beside the highway, I discovered, as I trekked around them in the green suit and matching green wheelie suitcase which had seemed appropriate attire in Aspen.

My jetlagged five am start was kicking in, my problem solving skills fraying. It will be fine, I said to myself, what an adventure, pushing down the rising panic. Another forty minute Uber beside a disconcertingly aggressive driver, in which I tried not to think about the firearms-per-person statistics of the States. I arrived at a strip lit motel so cheap it required a security deposit (because guests occasionally stole the towels, or staged a dirty protest, apparently). It was after midnight in an obscure area of the city and unhoused people clustered outside. My heart sank as I walked in, because the receptionist was a young man. I really could have done with a capable older woman with kind eyes in that moment. I was tired and far from home and in this dark strange city feeling increasingly visibly female, in ways women readers will recognise.

Still, nearly there, I thought, you can sleep soon and it will all seem better in the morning. I handed over my card. Declined. So was the next one. And the final one. The receptionist and I stared at each other. My mind scrabbled for an explanation but failed to get purchase. “Got any cash?” he asked. I had not. “Wanna call your bank?” I slumped down on a plastic chair, upped my roaming spending limit again and spent another forty minutes fighting my way through a range of labyrinthine robotic customer service portals, getting lost in the menus, misheard by the AI, increasingly desperate.

In that moment, I knew vulnerability in my body. The illusion of control which money and privilege usually gives me slipped, and I could see, suddenly, how precarious I was. My friends back in Aspen were asleep, my family at home not yet awake. I had no money and nowhere to go. The free Aspen food had all been eaten. Don’t let them kick me out onto the streets of Denver, I prayed. I’ll ask for sanctuary and sleep here, in this chair, under the fluorescent lights with the smell of burnt coffee and stale bagels. I thought about getting a third $70 Uber back to the airport, but didn’t know if that would have been blocked too.

My mind felt friable, all my normal capability gone. I wanted my mum. I put my head against the extending handle of my suitcase and wept.

The receptionist had disappeared into the back office for a while but at this point he reappeared and sat down beside me. He smiled, and handed me a thin paper napkin from the breakfast table for my tears. “Here”, he said. “I have been working out a plan with my manager, and we are going to try and take payment manually. And if it doesn’t work you should get some sleep and we will sort it out in the morning. Just don’t tell anyone”.

His name was Joquone, and I will never forget him. He mothered me, in that moment, offered me mercy. He subverted the corporate systems of the motel chain in order to help a vulnerable human being. Eventually, he was able to take payment (it was the hotel’s network which had been the problem, all along). When I woke up the next morning, we hugged and high fived like old friends.

My experience of precarity was fleeting, nothing compared to the unhoused people outside the hotel, or the everyday lives of the refugees in our church always living under threat of deportation. I hope it further softens my heart to their needs. But I did need help, and in receiving it, felt more fully human. There was a painful beauty in it, to the extent that I don’t really regret it. I think my soul needs these humblings. It is easy for me to offer hospitality from a place of power, to always be the helper. It is why I worry about the rich, feel compassion for the ways the formation of wealth disconnects them from others. To be fully alive we need to be helper and helped, knitted into webs of shared capacity and care, crossing the barriers of class, race, gender, age and all the other nonsense things we let divide us, to protect each other in our vulnerabilities. I could have had a frictionless journey, oiled by money and properly functioning technology and even now be at the book event I am missing. But I would never have met Joquone. And I am so glad that I did.

This is post is out of my usual rhythm (a week early), because I may not have time to write one in between book tour travels next week (unless I get stuck in another airport). It also does not have the usual audio version, for reasons of my mic being on the wrong continent. Thank you for being flexible!

What else I have been up to

Last Sunday (what even day is it?) I was on BBC One talking about Fully Alive. You can watch on catch up here - I’m the last segment.

This was a nice piece in The i paper about what we’ve learned through living in community.

More podcasts, with Guilt Grace Gratitude, Gravity Commons and Ancient Futures.

Oh my goodness. May we all be mothered. May we all mother. Amen.

I appreciate this very vulnerable and human story. It does something to our very souls when we recognize we need to be on the receiving end of grace--and allow ourselves to receive it.

And the travel woes sound familiar to me. As a middle-aged woman (like you, with a bunch of fearless adventures in my pocket from my younger years), I also recently had major flight delays and cancellations, also with the airline unable to put us into lodging for the night and everything in town booked up. Most of us, nearly the entire flight--including many much older than me--spent a long, hard, cold night in the airport. The amazing thing was that no one really freaked out. We all just took it in stride somehow, supported one another, and felt like a family when we finally boarded another flight in the morning. Even the flight attendants complimented us, saying how appreciative they were that we hadn't taken our plight out on them. They said we, a group of total strangers, had apparently "trauma bonded" and were helping each other get through a difficult time. We smiled in recognition.

Yes, allowing vulnerability to surface, extending and receiving grace and support, it does something to our souls. Something good.