Lessons from a “middle class commune”, part one.

We prefer “micro-monastery”, or intentional community, but whatever you call it, it’s taught me things you can apply anywhere.

Humans. Can’t live with ‘em, can’t live without ‘em, amirite? Our interpersonal relationships are the source of our greatest joys and almost all of our deepest suffering. Despite that, we leave most of the scaffolding for them implicit and intuitive, blundering around in the dark hoping to get lucky with a friendship, romance, team mate or neighbour. Basic relational skills are on the curriculum at no mainstream educational institution that I know of, and most of what we know we learn from narrative formats like films and novels (all of which have conflict as a key driver). This seems like madness. We might buy books or listen to YouTubers and podcasters, get help from a therapist, but it’s a patched together, personal pathway.

Generative AI chatbots hold out the lie of a life where we don’t need to deal with the difficulties of human relationships, but this is a giant, seductive, deadly mirage. There is no way for humans to flourish alone. Attempts to deny our irreconcilable interdependence is leading in increasingly bad directions. We are made for each other, and made by each other, and learning to navigate the very real challenges posed by other people’s humanity is how we grow up our souls. Or if the metaphysical language doesn’t work for you, we are hypersocial animals, primed from millennia of evolution to function really poorly as lone wolves. However you explain it, a failure to learn how to be together well is driving loneliness and despair, which as

and Stein Lubrano and and many other smart people have both been arguing persuasively, is in turn driving our political doom-spiral.Any attempt to flourish personally, build a better world or just survive what is coming requires these skills, for so long unhelpfully coded as “soft”. We need each other, are absolutely going to need each other more as the systems of our society creak and buckle, but actually existing in even semi-functional networks of mutual care and support is almost vanishingly rare. The good news is that it is entirely possible and extremely rewarding, although I learned it in an unusually radical way.

For the last nearly five years I have lived with my husband, kids and initially two and now three other adults. We have committed to each other at a fairly radical level: we have a joint mortgage, shared bank account and perhaps most radical of all, a shared kitchen. We pray, live and host together, up close. There is an article in The Times about us here, and one in The I here. We initially rented a home together during the pandemic, and when that experiment proved successful, managed to cobble together a complex financial model involving a wider group of supporters and buy a shared property in South London. We’ve been through Lockdown 3 in the UK together (four months of seeing basically no one else, all WFH and home schooling), job changes, multiple stretches of unemployment, major health stuff, faith crises, existential terror and a LOT of parties. We’ve had major building work done after a ceiling fell in, welcomed a new house mate and had many, many challenging conversations.

I love it. I write a bit more about our origin story in my book Fully Alive, but for today I wanted to share some lessons it has taught me. Living in any unconventional way forces a level of clarity and intentionality about areas we might otherwise leave vague, and these habits have hugely helped my relationships outside the house. You can apply them even if you are not yet (?) ready for commune life. This is likely the beginning of a series (we have learned a huge amount), but here are three fundamental lessons.

Clarity is kindness

Start with fun

Welcome friction

Clarity is kindness

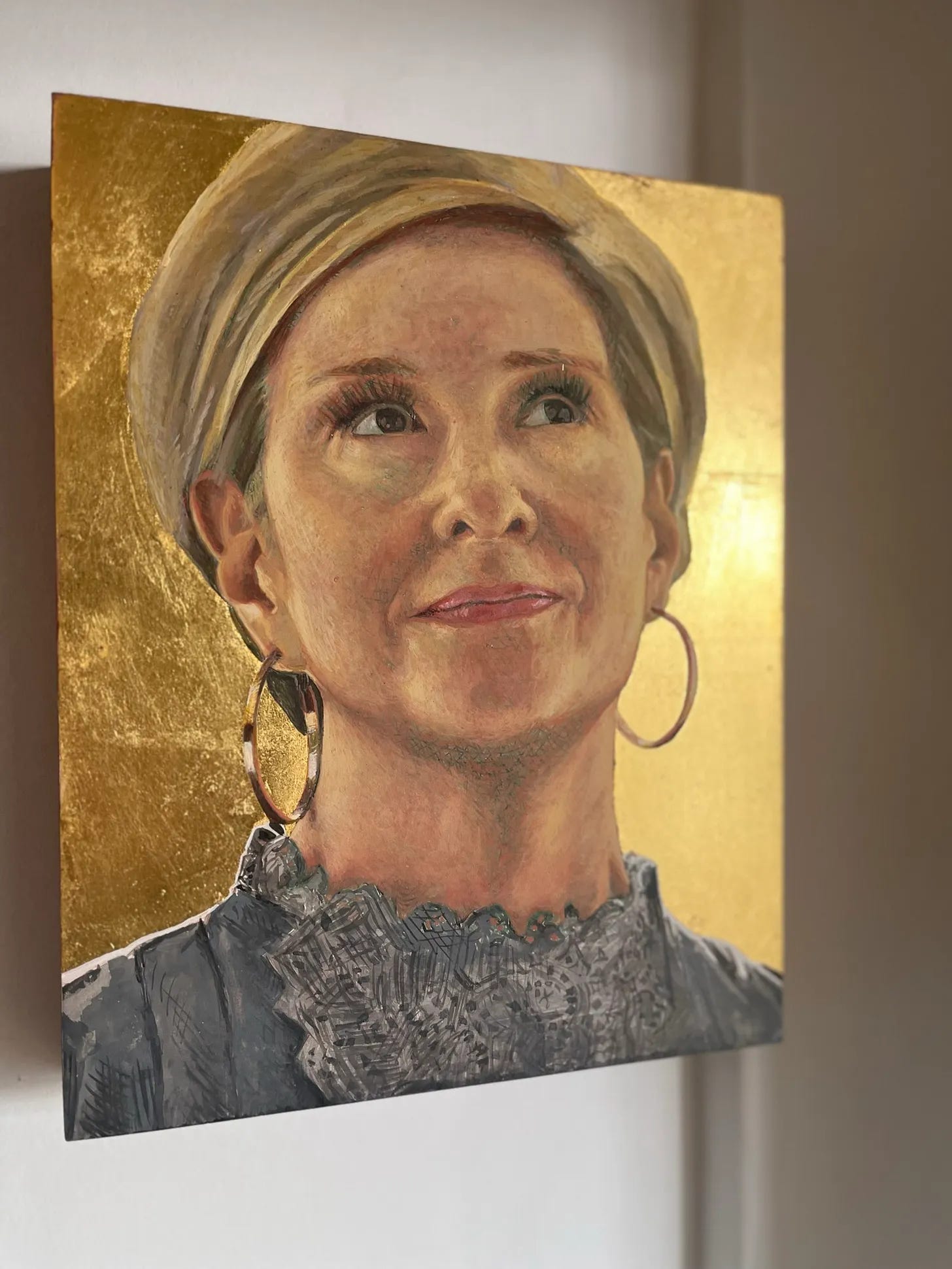

The image for this post is a painting of Brené Brown in the style of an icon, a tongue in cheek reference to how often her work comes up in our community. We don’t really have a name, being too small and deliberately not institutionalised to need one, but The Order of St Brené has been mooted. (It’s ok, we know she isn’t a saint).

Best known for her work on vulnerability and shame, Brown also writes insightfully on interpersonal dynamics and healthy organisations. The sayings we draw on most are “stay with the trouble” (sticky relational stuff can only be resolved by addressing it, not avoiding it) “the story I am telling is…” (this is how this situation seems from where I am, but I am aware that my point of view is partial) and surpremely, “clarity is kindness”.

Almost all of our hardest conflicts in the house can be traced back to a lack of clarity. It can be hard to be clear even to ourselves about what we want or need, why we are reacting as we are. Part of the work is in seeking more clarity, personally. The skill to read internal weather accurately is a great asset in a community house mate.

Sometimes though, we are clear internally and have not made that explicit. So much of human communication is implicit, gesturing to things, assuming understanding, dancing around issues. Perhaps especially British, and I gather, Canadian communication. We have some weird hard wiring around politeness. The guiding philosophy of communication here is more like “obfuscation is kindness”. We sense if we leave things vague there is more room to manoeuvre, we are less likely to hurt someone’s feelings, make things socially awkward. What actually happens is that the vagueness provides a perfect breeding habitat for assumptions and misunderstandings. My Dutch friends find this polite vagueness hilarious and frustrating. Their ease with speaking directly can feel rude in comparison, but my goodness is it easier to be in relationship with someone you are not having to second guess.

What does this mean, in practice?

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Fully Alive by Elizabeth Oldfield to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.